Advanced Cancer

Advanced Cancer

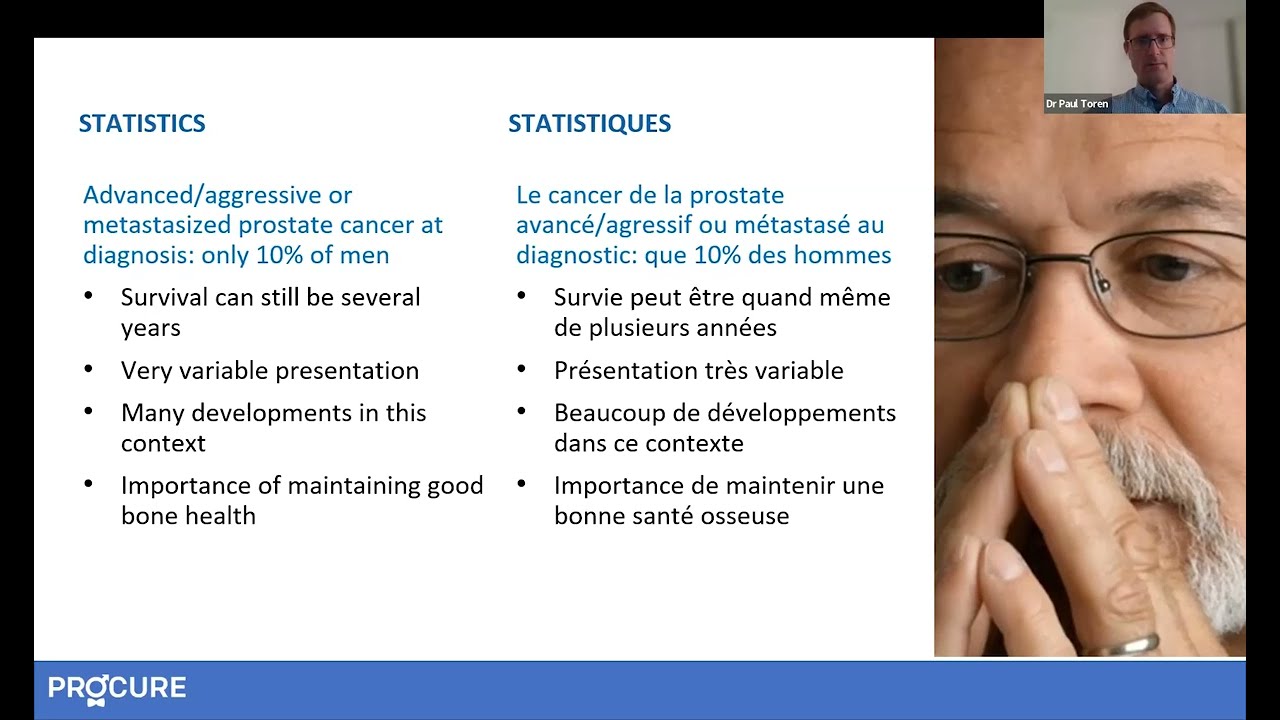

Some of these cancers can be cured. Others will be controlled; the various treatments can successfully control the progression of your cancer for several years. In the presence of metastases, they can reduce your symptoms and pain. For cancers that cannot be cured, specialists increasingly agree on the chronic nature of this disease thanks to advances in research and the emergence of new molecules.

Targeted therapy and inherited mutations

Have your doctor talked to you about targeted therapy for your prostate cancer? It pays to know the facts so you can understand the situation and decide what’s best for you. Let’s take a closer look together

The term “advanced prostate cancer” does not describe just one type of disease, but several. It can be one of the following types of prostate cancer.

Locally advanced cancer –When it has started to spread beyond the prostate but has not gone too far. It may have barely breached the capsule boundaries, but it may also have reached neighboring tissues, such as the bladder, external sphincter, and rectum. For more information, click here.

Recurrent cancer –When it reappears after initial treatment (surgery, radiotherapy/brachytherapy) with or without metastases. For more information, click here.

Cancer with metastases –When it has spread to other regions of the body, distant from the prostate. Most often, prostate origin metastases establish themselves in the pelvic lymph nodes and bones. For more information, click here.

Castration-resistant prostate cancer or CRPC– When it continues to progress despite hormone therapy. For more information, click here.

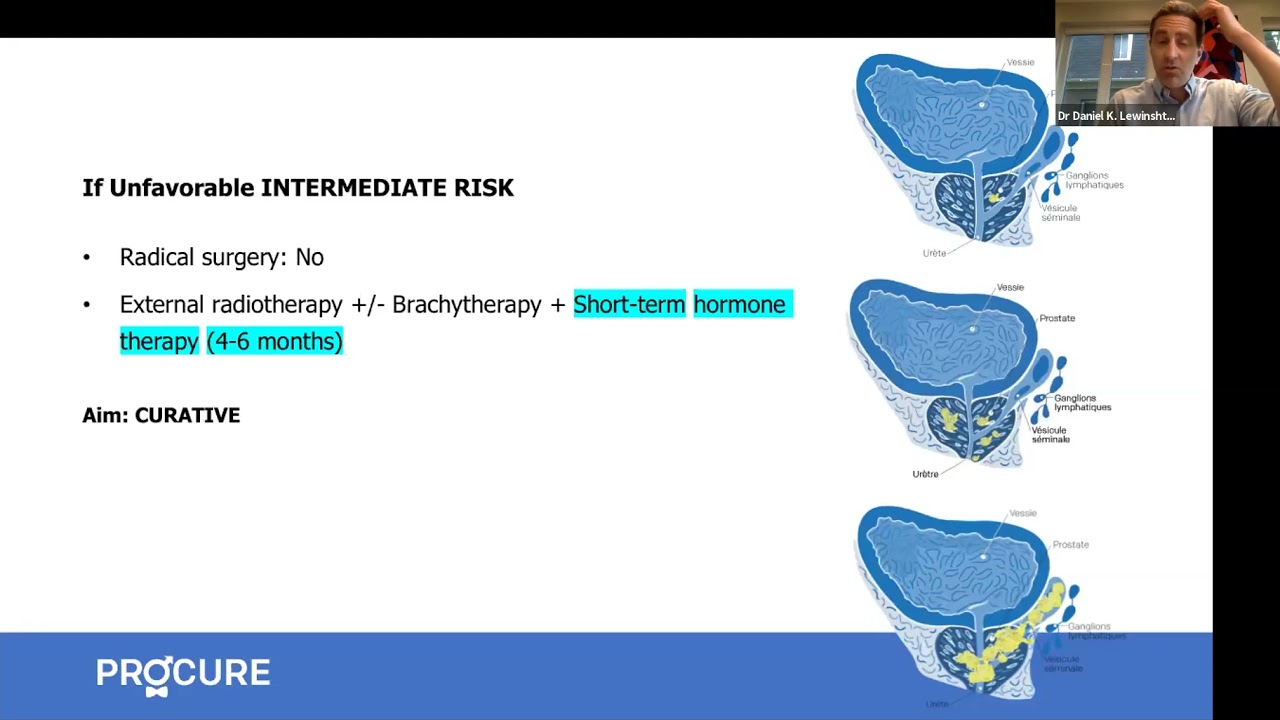

The goal of treatment

The chosen treatment will depend on the type of advanced cancer and aim to either cure it or slow its long-term progression. The choice of treatment will depend on various factors.

- Your age and life expectancy

- Your Gleason score, stage, and PSA level

- Your past treatments

- The location of your recurrence, if applicable

- The presence of diseases such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes

- Your symptoms

- Your personal preferences

Additional palliative treatments may be added to reduce your symptoms or bone pain. To relieve pain, bone and other pain, analgesics, treatments to strengthen the bone, and even palliative radiation therapy are prescribed. If you have metastatic cancer, you will also need to take calcium and vitamin supplements D.

Bone health

Bisphosphonates

- Bisphosphonates, such as zoledronic acid (Zometa), can slow or halt the progression of bone destruction caused by metastases, thus reducing the risk of fractures.

- Used in patients with CRPC with bone metastases, bisphosphonates help reduce the risk of complications from metastases and limit the need for analgesics and palliative radiotherapy.

Biological Agent

A drug called denosumab (Xgeva) can be used instead of bisphosphonates to slow or stop bone loss caused by bone metastases.

- Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody that recognizes and attaches to what is called the RANK ligand, which is largely responsible for stimulating the cells that weaken bones, leading to bone fractures.

- By targeting and blocking RANKL, this degradation is slowed down.

- It has actually been shown to be slightly more effective than zoledronic acid in reducing bone complications in men with metastatic CPRC.

- Furthermore, it has also proven to be very effective in reducing bone loss (and thus preventing osteoporosis caused by medical castration) and the risk of fractures.

Palliative external radiation therapy

The radioactive rays of radiotherapy destroy the cells of metastases in the bone that cause pain (in the spine, hips, back, etc.). This does not change the course of the disease, but quickly relieves the patient, strengthens the bone, and consequently helps reduce the risk of fracture at the irradiated site.

Usually, palliative radiotherapy is used when pain relievers are not sufficiently effective or when there is a risk of bone fracture. However, the same spot cannot be irradiated twice. Therefore, often, doctors use radiotherapy as a last resort.

If pain returns to the irradiated area, pain relievers and treatments aimed at strengthening bones can provide some relief. It should be noted that these medications can be used at the same time as radiotherapy.

Palliative surgery

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) – Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) may be an option for castration-resistant prostate cancer. This type of surgery helps relieve symptoms of urinary obstruction caused by prostate tumor.

Learn more about palliative care

To learn more about symptom control and managing financial, family, or psychological issues, click here.

Participating in a clinical trial

One way to access new treatments before they become widely available is to participate in clinical trials.

A clinical trial is a research study that uses volunteers, called participants, to test new ways of preventing, detecting, treating, or managing prostate cancer or other illnesses. Some clinical trials help determine whether or not a new drug or device is effective and safe.

Participating in a clinical trial is a valuable contribution to research as clinical trials answer important questions that can lead to better health outcomes. Participation can be a good way for participants to access free treatments. To learn more about clinical trials speak with your healthcare team.

Finding a clinical trial can be a difficult and tedious process. To address this issue, our partner Q-CROC developed Onco+, a free support service available to anyone looking for an oncology clinical trial in Quebec.

If you would like to learn more about oncology clinical trials in Quebec and consider whether participating in a clinical trial might be an option for you, please visit the website of our partner Q-CROC.

Additional clinical trial site:

- Canadian Cancer Trials: Canadian Urological Association

2023 Scientific Expert Opinion

Here are two video clips that might interest you with Dr. Aly-Khan Lalani, Medical Oncologist at the Juravinski Cancer Centre and Assistant Professor at McMaster University, in Ontario, Canada, following the ASCO-GU scientific conference in 2023:

Questions for the medical team

To get answers to your questions, you need to prepare. Before meeting with your doctor or nurse, make a list of questions to ask. Making a list of questions before your appointment with your doctor can be a way to put on paper what concerns you.

- Write down the most important questions on your list first.

- Bring a loved one with you.

- Remember that this meeting is not your only chance to ask questions.

- Try to accept that uncertainty exists; medicine does not have a definitive answer to all questions.

We invite you to visit our page Questions to ask your doctor and healthcare team about advanced prostate cancer. Asking questions will open communication, provide information tailored to your situation, and reduce the stress associated with understanding your treatments.

Additional Information - Treatment options

Advanced prostate cancer treatments strategies

Strategies for treating advanced cancer have significantly evolved, offering new options and hope for patients.

Prostate Cancer Study Results Summaries (2023 ASCO-GU)

Summary of clinical trial results on promising prostate cancer research.

Advanced Prostate Cancer Triple Therapy Study Results (2023 ASCO-GU)

Clinical trial results on triple therapy for advanced hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

Expert Opinion: Prostate Cancer and Hormone Therapy

What you need to know about hormone therapy and how to manage the side effects of this treatment.

Prostate cancer and nuclear medicine

What about nuclear medicine? Is it suitable for your situation?

Nuclear imaging technologies

Has your doctor suggested prostate imaging tests? Explore options like PSMA PET scans.

Targeted therapy and inherited mutations

If you have a specific genetic mutation, you could benefit from new targeted treatments.

States of prostate cancer following treatment

Do your recent tests show an increase in PSA levels? It could indicate a recurrence.

The role of hormone therapy

Has your doctor recommended hormone therapy? This video is for you!

Advanced prostate cancer treatment strategies

Strategies for treating advanced cancer have significantly evolved, offering new options and hope for patients.

Advanced prostate cancer treatment

Advanced prostate cancer encompasses various conditions, including metastatic, recurrent, and hormone-resistant forms, each raising different questions and concerns.

When prostate cancer comes back

A recurrence is when the cancer returns after treatment. The main question is, “What’s next?”

How to treat advanced prostate cancer

Advanced prostate cancer encompasses various conditions, including metastatic, recurrent, and hormone-resistant forms, each raising different questions and concerns.

All about hormone therapy

Hormone therapy can reduce tumor size, control cancer, and prolong life. Is it the right treatment for your cancer?

Q-A – New therapies for advance prostate cancer

In this interview, we answer patients’ questions about new therapies for advanced prostate cancer.

Am I a good candidate for radioligand therapy?

Find out if you are eligible for radioligand therapy for prostate cancer, how the treatment works, and the precautions to follow.

Radioligand therapy: a promising option

Learn how radioligand therapy helps slow advanced prostate cancer and why access to this treatment varies across Canada.

Biomarkers: guiding treatment decisions

Discover how biomarkers personalize and guide prostate cancer treatment decisions for each patient.

Biomarkers: better understanding prostate cancer

Learn how biomarkers enable more precise monitoring and treatment of prostate cancer.

A recurrence does not mean the end

Discover the available treatments, new targeted therapies, and the next steps in managing a prostate cancer recurrence.

The effects of hormone therapy and PARP inhibitors

Learn how hormone therapy and PARP inhibitors work in your body and what side effects to anticipate.

Bone scan: detecting bone metastases

When prostate cancer progresses to an advanced stage, it can spread to the bones. This is where a bone scan plays a role.

Prostate cancer: better understanding your tests

Understand the purpose of your tests (PSA, MRI, PSMA PET scan, biopsy, bone scan) to better navigate them.

Prostate cancer: better understanding hormone therapy

Which approach is better: continuous or intermittent hormone therapy?

Sources and references

Last medical and editorial review: April 2024. See our web page validation committee and our collaborators by clicking here.